Parents’ dreams and challenges hold lessons in hope, joy and resilience

By Barbara Aggerholm | Family Photographs

My Danish-born father made three promises to his bride.

Someday, they would dance the Vienna Waltz in Vienna; they would bring home the Little Mermaid from Denmark, and he would build their dream home.

Never mind that my father couldn’t dance a step, though my mother loved to dance and took lessons with her sister in Toronto when they were young.

Never mind that Paul Aggerholm and Madeline McIvor were both children of hard-working, thrifty parents – my father’s father because he had been swindled out of his business by his partner in Denmark. My grandparents moved their family from Denmark to the little town of Rodney, Ont., where my dad used his fists and his superior baseball skills to get accepted. My mother’s father had farmed on rocky Manitoulin Island until he and his wife moved to Toronto where, to support six children, he worked at the Nordheimer piano factory.

My grandmother’s Nordheimer piano sits in my living room, reminding me of the lovely touch for which she was known when she played in Manitoulin Island churches.

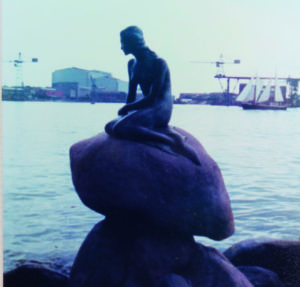

And never mind that the bronze sculpture of the Little Mermaid, a tribute to Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid” fairy tale, sits on a rock by the water in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Later in life, I learned that each of us has different memories of our growing-up years. How we colour them is very individual.

It was after I was an adult that I remembered and appreciated the fulfilment of Dad’s promises. When we were children, sacrifices along the way might have made me and my two siblings forget.

Long before the dream home, my brother, sister and I lived in small towns with our parents in apartments above the banks. My bank manager father was saving money and working his way up the ladder. Our mother, a gentle teacher who started her career in a one-room schoolhouse near Toronto, would eventually find work where we lived. But she’d be uprooted whenever my father got a promotion and was transferred to another branch in a new town.

She cried in the piano room of our rented house, a rarity among our lodgings, after he came home to announce the latest move to a small, wintry town on the Bruce Peninsula. After years of supply teaching, she had landed a full-time teaching job that she loved in a local elementary school. Now, she’d have to apply again to another school in another town.

We learned later that my father could have accepted a banking job in Bermuda, but turned the transfer down because he believed his children would not get the education he wanted for them. From the day we were born, we had certificates on the walls of our bedrooms telling us that our parents were paying into a scholarship plan for our university careers. There was never any doubt that we would leave our small towns to go to university. My sister has a PhD in psychology and is a professor emeritus and former dean of graduate studies of an Ontario university; my brother, now retired, has a degree in geography and was an environmental planner; I have a master’s degree in journalism and 40 years in the profession.

When my father was a teenager, a coach wouldn’t add him to his ball team because he didn’t speak English. But he didn’t give up.

“Let’s see what you can do,” said the coach of a much-older team after learning of his rejection. My father hit the ball out of the park, and he was invited to join the senior team. His skills got headlines in the local newspaper and a too-late offer from the coach who had dismissed him earlier.

Then the Second World War came. My father, who was with the Royal Canadian Air Force, worked all over the United Kingdom with the RAF on aircraft navigation systems used in anti-shipping and anti-submarine operations. During the war, most of his teammates on that small town team were killed. My father never played baseball again.

While he was overseas, he sent home money to help support his father, mother and sister. After the war, he would have liked to have studied to be a doctor rather than become a banker, but there was no money for a university education.

He was a bit of a renegade in the banking business. He sometimes argued with head office about a loan that he would grant to a struggling beef farmer whom he was confident would pay it back. As an adult, I understand better why we children were told to be quiet at the dinner table on Friday nights when we wanted so much to talk about our day. He came home exhausted.

Homemade pies showed up at our door some days – thanks from farm families he’d supported. Later, when he was 90 years old, he talked about an elegant woman who introduced herself to him in a coffee shop. “Remember me?” she asked. He’d given her a loan when no other bank would. She was a young, Indigenous woman who’d left her abusive husband on the reserve. The money my father lent her was for her education. She was now a school board superintendent.

“Thank you for believing in me,” she said.

He was respected for his intelligence and feistiness, and upon his retirement, he and my mother were invited to a dinner in Montreal hosted by the man at the top of the Royal Bank of Canada.

The dream house, in the town where they eventually retired – my father the bank manager and my mother the kind teacher of students with Down syndrome – was built while we were living above the bank. That apartment was roomier than others that we had lived in, but it contained the same feeling of dread whenever the bank alarm rang at night and my father went downstairs to investigate.

The house was built overlooking beautiful Colpoy’s Bay. On snowy mornings, my brother and I would head up the hill before school to shovel off piles of snow on the unfinished floors before the workers arrived.

The house took shape, using the ledgerock of the area, over two lots. There were two vast, stone fireplaces made by a local artisan. Floor-to-ceiling windows stretched across the front of the house at a time before houses of glass were popular.

There, my mother would gaze out at the water.

There, in 1983, my mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease before she’d retired from teaching.

There, in 1983, my mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease before she’d retired from teaching.

“In time, you won’t recognize your husband.” That’s how the young women broke the news after testing her at a Toronto hospital. Begin at 100, subtract by seven, they’d asked her. Now do this and then do that. “Didn’t enjoy it,” she wrote in her diary. Then she was sent home. There was none of the counselling that is done today; none of the research and drugs that would have helped my mother and father navigate the frightening world of a future without memory. Just, go home, get by. “They said that . . . it may be a complete loss of memory,” she wrote. “I’m only 63. I think I’d rather die.”

But my mother and father packed in as much living as they could before Alzheimer’s ultimately robbed her of speech and mobility. They danced that Vienna Waltz in Vienna, Austria, and I imagine that no one cared where they placed their feet. They brought home the Little Mermaid. The graceful Royal Copenhagen figurine was carried in my mother’s luggage after a visit with relatives in Denmark. When my parents went through Customs, my mother didn’t remember that it was there, so she had nothing to declare. “Oh, Paul,” she would say with a smile when my father told that story upon their return home.

They lived life as fully as they could, though it tugs at my heart now to see the lists and diagrams in my Mom’s diary that helped her remember who was who and what was what.

She even planned our wedding in my Ontario hometown while I lived with my fiancé in Brandon, Manitoba, where we’d landed our first full-time journalism jobs. I don’t know how she managed it, and I had no idea then, living so far away, that it would have been such a struggle.

Her little notepad is filled with loose bits of paper with checklists and more checklists, some of them repeated again and again.

We had a truly beautiful wedding, complete with a dinner reception in a nearby lodge arranged by my father featuring the best beef that Bruce County could offer.

That sun-filled dream home on the escarpment was my parents’ home for several years, until my mother could no longer manage its care, let alone her own, and was forgetting our lives together.

They moved, returning to the Lake Huron town where my father had once worked and where my sister and I were born. Eventually my father, after kind neighbours had done everything they could to help him care for her at home, placed Mom in the long-term care ward of the hospital.

Every day, my father walked several kilometres from their apartment on the harbour to the hospital on the hill to help feed my mother and, on an old cassette player, play the classical music that they both loved. This was long before the research that showed music is among the last things we forget. We already knew it by the way my mother smiled and hummed.

Sometimes, my father would take my mother out to the cottage that he and my grandfather built on lakefront property, one of the first cottages on a former farmer’s field. There, my mother would enjoy listening to the rhythmic waves hitting the beach.

She would be surrounded by familiar souvenirs of summers we spent there. Every June, when we were young, my family would make its exodus to the lake. The car was loaded with two adults, three children, a dog, a cat, two turtles and a bucket of goldfish at my feet. At the end of a weekend, my father would return to the bank while we went on beach walks, collecting fishing floats and driftwood that we hung on the wall.

My mother and my aunt, whose family built a cottage next door, would visit each other after putting us to bed. We soon learned that they listened through an intercom system between the two cottages. “Get to bed,” came the booming voice from nowhere when they heard us stir. It was like the voice of God and we scrambled back under the covers.

One summer, my mother saved the life of a little boy. The waves had swept the boy over his head in the water and the riptide was pulling him under. I can picture my mother, while others were frantic, taking off her blouse and purposefully wading into the water. Of all the emotions overwhelming me, I’m ashamed to say I was embarrassed for her. Only for a minute. I watched her swim to the boy and throw one end of her blouse to him, calling for him to take it. She grabbed him and pulled him back to the beach. I was awed by her sense of calm. Standing there in her bra, she was my hero.

My mother collected so many stones from the beach that my father began pitching them down the hill, complaining that the cottage was sinking from the sheer weight of them all. When I visited the cemetery many years later, I learned that he had retrieved some of those same stones and placed them on her monument.

My father, in his 90s, died several years ago, but I can still hear him chuckling while my sister and I struggle to put the shutters on the windows each fall. My sister holds the ladder while I try to figure out which screwdriver to use. One kind of screw would have been too simple!

The cottage is my anchor.

The cottage is my anchor.

After my mother died, my father would often talk about those three promises; how they danced in Vienna though his feet stepped on hers; how the Little Mermaid figurine sat in a place of prominence in their living room; how he built her dream home.

I learned lessons from them that have stayed with me while my own children grow up and while my husband and I navigate our retirement years: hardship doesn’t change a promise; you dance no matter what; you seek moments of joy, especially when they seem hard to find.

And when things get tougher than you ever thought they would, you hold on for dear life.