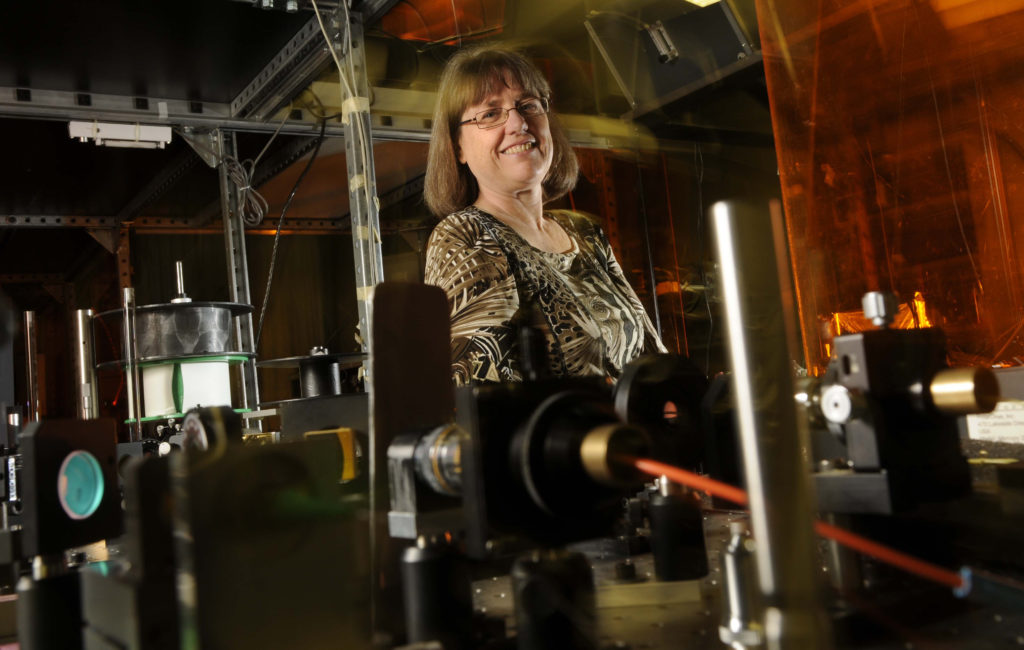

World sees University of Waterloo professor Donna Strickland differently after winning Nobel Prize in physics

By Laura Booth

By Laura Booth

Donna Strickland’s life has been total “madness” since Oct. 2, 2018.

She’s dined with royalty and chatted with political leaders; she’s been interviewed by international media outlets; she is booked for speaking engagements into 2020; she’s watched enrolment to her laser class at the University of Waterloo double. It seems everyone wants a piece of her time.

But perhaps winning the Nobel Prize should be like that, especially considering Strickland is only the third woman in history to be awarded the prize in physics. She follows the great scientific minds of Maria Goeppert-Mayer, who won in 1963, and Marie Curie, in 1903.

“It’s hard not to focus on the institutional implications of a woman being so globally recognized for work that she’s done,” says Hannah Dykaar, Strickland’s daughter, who is doing a PhD in astrophysics. “And for me, I’ve always been inspired by her, but it’s exciting now that so many people also get to be inspired by her.”

Strickland and her former PhD supervisor, French physicist Gérard Mourou, were awarded one half of the physics prize for their groundbreaking work in laser physics. American scientist Arthur Ashkin won the other half of the award.

“It’s less winning a prize and more of being anointed,” notes her husband, Doug Dykaar, an electrical engineer. “The entire world now looks at Donna differently, everybody from people at the university, to the public, to people in the field. It’s amazing to see the transition.”

Strickland’s charismatic personality and sincerity have also received attention, which is no surprise to her husband, daughter and son, Adam.

“I think … she comes across differently than people expect a scientist to,” Hannah says. “She’s very down to earth and very funny and, I think, relatable.”

For Doug, it’s obvious why people are drawn to his wife.

“I’ve known Donna for 30 years, and it seems the world is finding out what I’ve known all along. There’s a genuineness, if that’s a word, that clearly comes across.”

Still, winning the Nobel Prize is a particular kind of honour.

“I was in a fog the whole day,” Strickland recalls in an interview.

That October day started with a 5 a.m. phone call from Sweden to inform her she had won the physics award. Nine hours later, thunderous applause greeted her as she walked into a packed University of Waterloo boardroom. A crowd of reporters, photographers, students, faculty and staff rose to their feet to greet the new Nobel Prize winner.

“I remember saying a little prayer to my poor dead mother saying, ‘I’m sorry I’m not wearing a suit for this press conference,’ ” Strickland says with a hearty laugh.

She took a seat at the front of the boardroom and turned her attention to the large gathering.

“I was surprised at the crowd that was there,” she says. “When (physics professor) Robb Mann stood up to say how proud the whole department was, that’s when I saw pretty much my entire department was there and beaming at me. That almost choked me up.”

Strickland’s solid reputation in her field stretches back decades.

Strickland and Mourou developed a technique called chirped pulse amplification, which produced lasers with high-intensity, ultra-short pulses. Since publishing their findings in 1985, the technique has been used to create lasers for a number of applications such as laser eye surgery.

“Her work made my research and thousands – if not millions – of other researchers and also surgeons . . . made their work possible,” says UW professor Joe Sanderson, who runs a laser lab next to Strickland’s.

It was her work that prompted Sanderson to leave his home in England years ago to teach in the same department as Strickland at the University of Waterloo.

“That work was done in the mid ’80s,” he says. “And when I came into the field, which was in the ’90s, she was already famous for that.”

Donna Strickland met her PhD supervisor, Mourou, at the University of Rochester in New York State. It’s where she would complete her award-winning work. It’s also where she met her future husband, Doug Dykaar.

One of the first tasks she had to complete for Mourou in the 1980s was building a cover for a laser.

“He took me into this one laser lab and there were these three guys from electrical engineering working with their supervisor at the time,” Strickland explains. “They had a laser without (a cover) so it wasn’t safe.”

One of the students in the lab that day was Dykaar, a Long Island, N.Y., native who was two years ahead of Strickland in his program.

“I still remember being introduced to her in the dark, because the lights were off and the laser was running,” Dykaar says.

Donna became one of the “laser jocks,” a moniker the graduate students at the school gave themselves.

“I think it’s because we thought we were good with our hands,” she says. “As an experimentalist, you need to understand the physics, but you also need to be able to actually make something work and lasers were very finicky in those days.”

In a speech delivered at the Nobel Banquet in December 2018, Strickland explained that Mourou “dreamed up the idea of increasing laser intensity by orders of magnitude.”

“He did it while he was on a ski trip with his family — he probably shouldn’t have been thinking about lasers, but he just couldn’t help himself,” she said. “It was my job to take Gérard’s beautiful idea and make it a reality.”

For a year, Strickland was busy building a pulse stretcher, then a laser amplifier, then a pulse compressor to bring this crazy idea to life. It was science for the sake of science — she was creating a laser without a specific application in mind.

When it finally came time to measure the laser, she needed the help of colleague Steve Williamson, who had the proper camera for the job.

“He wheeled his streak camera into my lab one night and together we measured the compressed pulse width of the amplified pulses,” she said at the banquet.

“I will never forget that night. It is truly an amazing feeling when you know that you have built something that no one else ever has and it actually works.

“There really is no excitement quite like it, except for maybe getting woken up at five in the morning because the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences also thinks it was an exciting moment for the field of laser physics.”

After her PhD days, Strickland worked as a research associate at the National Research Council Canada and as a physicist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. She joined the University of Waterloo in 1996 to lead an ultra-fast laser group developing high-intensity lasers. She has also served as president of the Optical Society and has won several awards and fellows.

Now she has the big one. The Nobel Prize.

Her sister, Anne Strickland, describes Donna as “a straight-shooter.”

“I think people appreciate the honesty.”

Anne says their loving parents, Edith and Lloyd, who died years ago, “would have been over the moon” at Donna’s success.

Anne mentioned their parents as she gave a toast to her sister last Thanksgiving, just days after Donna’s Nobel win. In the toast, Anne said she and their younger brother, Rob Strickland, would stand in for their parents at Donna’s Nobel ceremony.

“She had me tearing up,” Donna says.

It was Anne who would be tearing up in December as she watched her 59-year-old sister walk into the Nobel Banquet in a stunning red dress and on the arm of the King of Sweden — the first in line in the procession.

“It was just a moment when you think, you could never have imagined this,” Anne says.

Donna and her siblings — Anne, who is a mechanical engineer, and Rob, who is the president of Fidelity Investments Canada — were born and raised in Guelph.

Their father, Lloyd, a gentle and quiet electrical engineer with General Electric Canada, had moved from his home in Cape Breton to work with the company in Guelph. That is where he met Edith Ranney of Milverton on a blind date. Edith would teach history and English at Guelph Collegiate Vocational Institute.

Anne Strickland says their parents were lifelong learners. The family would often go on car trips, and Edith would always prepare informational binders for each of the towns and cities they would find themselves passing.

“Every day she could tell us ahead of time what we were going to see in the background,” Anne recalls. And coming across a city with a mine meant an automatic pit stop to explore.”

While Edith and Lloyd were not alive to see their daughter deliver the Nobel lecture she spent two months working on, or to watch her on stage receiving her Nobel from the King of Sweden, they may have known something special was in store for their daughter before anyone else did.

Or so Donna recently learned.

“Some of my husband’s relatives, they said to me … ‘I remember your dad at the wedding and saying he thought you’d get the Nobel,’ ” Strickland says. “I can’t believe that’s what my dad was saying at my wedding.”